In the early stages of 2023, Generative AI (GenAI) blew up in our faces by threatening to take away our (as humans') exclusive right to "authorship". One of the many questions this raised was whether we shouldn't compensate authors whose works were used by the GenAI1. We suspect that the origin of this question was closer to a protectionist tariff on creativity than to the rigorous application of the law. Nevertheless, it is worth addressing.

Although it does not establish a right of remuneration in favour of artists whose works have been integrated in datasets training of an GenAI model, in the current Article 53 of the final version of the IA Act if provides as follows:

“Article 53: Providers of general-purpose AI models shall:

d) draw up and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary about the content used for training of the general-purpose AI model, according to a template provided by the AI Office.

It seems reasonable, therefore, that there is some reason for the AI Act to ask general-purpose AI providers for a summary of their datasets, and this reason may well be the future creation of a remuneration right as described above2.

How could we articulate this right to remuneration?

Some authoritative voices call for the application of mutatis mutandis3 the current mechanics of Collective Management Organitzations. Others, without being so forceful, do ask for a minimum recognition of the works used by Gen AI. To cite one among many, we have the “A.I. : Open Letter”, signed by numerous organisations representing the interests of authors or artists, among which is the SCAPR, the international federation representing Collective Management Organisations for Interpreters.

The fourth point of the letter reads as follows:

“4. The credits must be recognised

Creators and performers should be entitled to recognition and credit where their works have been exploited by AI systems.”

The question is immediate: When we talk about morally recognising the author of the work "used" by the AI model as if it is a matter of remunerating him for that use, what use are we talking about? Let's look at it in a little more detail.

The use of works for the training of Gen AI models

To answer this question it is essential to analyse, from a technical point of view and with the greatest possible abstraction, what exactly is the use [and purpose of that use] that has been made of the works [and what are not works] to train the underlying Gen AI models that have triggered the discussion we are examining here.

As we have already advanced in this article, Gen AI model training involves, roughly speaking, providing to a Machine Learning (ML) algorithm with an astronomical number of representations of reality, including, but not limited to, copyrighted works. What happens to the input materials thereafter is that the algorithm identifies (usually in an 'unsupervised' way) the underlying patterns of these representations of reality. These underlying patterns are incorporated into the algorithm (this is what we refer when we say that the machine 'learn') in a mathematical formulation, so that subsequently, and through this formula, the model is able to generate new content. Once the model has been trained, the input materials are no longer useful (and, consequently, could be eliminated).

So, for the purposes of this paper, what has the ML algorithm learned (and therefore used) to provide the Gen AI model with creative capacity? Precisely everything that is not protected by IP rights, namely the underlying patterns of tens of millions of representations of reality, whether in text format for models focused on text generation (see GPT-4, from OpenAI), image (see Midjourney Model v6, from Midjourney), or video (see the brand new Sora, also from OpenAI).

And the next logical question to ask is, what exactly are we talking about when we refer to the underlying patterns of materials? In the case of text, the uncountable probabilistic patterns that emerge from hundreds of millions of concatenations of words (i.e. texts); or, in the case of images, the same kind of patterns found in hundreds of millions of different compositions of pixels (i.e. images). In any case, those patterns are the ones that the ML algorithm is able to identify from a probabilistic-mathematical point of view, but in no case from the point of view of consciousness, emotions and deep understanding, which is how we humans supposedly express ideas. For this reason, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, when asked on numerous occasions about the risk of hallucination of AI models (that AI's invent things), says, with some humour, that in reality, AI models are always hallucinating, because there is no concept of ‘truth’ or ‘certain’ in this field, only approximations with a high degree of probability of being correct as far as human standards are concerned. Thus, no matter how much we call this field Artificial Intelligence, it has practically no ‘intelligence’ in the human sense of the word. That we think intelligence exists is just an illusion.

An example of a pattern: grammar. Not as you understand it, reader, but from a mathematical perspective. That is, while you know that ‘Artificcial’ is not written with two c's, because that's how the English language expresses that sound, ChatGPT simply considers it unlikely, because it has (hopefully) never seen the term ‘Artificcial’.

Back to the supposed right of remuneration for the use of works for the training of IAG models

Therefore, this remuneration does not seem to be the best option to meet the challenge represented by Gen AI, since:

- It happens only once, and not even in direct connection with an act of economic significance (such as the generation of content), and;

- The huge amount of data used makes it impossible to assign anything other than a ridiculously low economic value to the use of a particular work.

Unfortunately, however, we cannot opt for remunerating the generation of works either, as the technical process underlying the generation does not allow this, since the model itself does not know which works have been most decisive for the training that has been useful for the generation of the content.

To generate content, Gen AI starts from a mathematical formula, achieved through learning through works that, once used, can be eliminated as unnecessary. The content generated is not directly related to the content of the training. Succinctly, we could say that AI does not cite sources, because it basically has no sources (in the sense of those considered as such individually, and as we humans conceive them).

Therefore, once the training phase has ended and the pre-existing works have been eliminated, there are no more acts of exploitation of the pre-existing works. The generation of content would be the act that we would intuitively want to use as a reference for remunerating artists, since it is where there is apparently a greater connection between the exploitation of pre-existing works and the generation of new ones, especially if, we insist, apparently, we can guess a connection between one and the other. The truth is that on a technical level there is no such connection.

Another totally different case are those cases in which the Gen AI plagiarises copyrighted images.

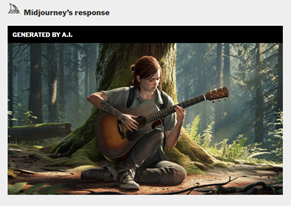

Note: Mr. Southen's entire prompt was: “the last of us 2 ellie with guitar in front of tree –v 6.0 –ar 16:9.” The prompt specifies Midjourney’s version number (6.0) and an aspect ratio (16:9).

It is not necessary to cite the law or any monograph on the concept of plagiarism to see that the decisions made by the IAG, which are not included in the prompt (such as the way the protagonist's legs are crossed, which cannot be extracted from the instructions in any way), have their origin in the original image.

What you have just read is false.

Yes, sorry, it sounded great, but it's false. What is true is that the AI-generated image, objectively, reproduces in a non-accessory way the original elements of the pre-existing work, but, and here is the counter-intuitive part, it does not make a subjective copy. The process of creation is, in fact, independent.

To understand what is happening in this case we need to go back to the fundamentals of the technical process we examined earlier. And indeed, as counter-intuitive as it may sound, what Gen AI model has learned is not the cross-legged arrangement as such, but the thousands of patterns underlying the combination of pixels in this and hundreds of millions of other images that result in an image that, from a strictly probabilistic-mathematical point of view, fits the user's request.

And what is really fascinating about the state of the art at the moment is that, through increasingly simple prompts, we can produce a level of detail that practically reproduces what we have in mind. But, we insist, the fact that the image is so similar (many would agree that it is identical) to the original, is nothing more than a kind of illusion in our eyes, reflecting a spectacular result of the progress made in this field, and that specifically in this case, it is provided in a way that, in this context, invites us to think that it is plagiarism, but from a technical point of view, it is not.

Therefore, in the minority of cases where the AI does indeed (legally) plagiarise and invade the monopoly of the exploitation rights of a pre-existing work, as in the case above, its author may be able to claim compensation.4, a matter worth addressing individually in another article.

And, on the other hand, in the vast majority of cases we will not be able to establish a right of remuneration to the authors of the pre-existing works used to generate the content, since technically these pre-existing works have neither been used directly nor is it possible to individualise their contribution to the mathematical formula used by Gen AI models.

What do we do then?

Both this article and the hypothetical right of remuneration for authors of pre-existing works are based on the premise that AI is likely to replace artists to a large extent. Why? Because AI, like artists, produces content.

Is this really what artists do - produce content? Does it make sense to analyse Keith Haring's or Hoke's work from a purely patrimonial perspective? The principles of European copyright law tell us no. Patrimonial rights are a consequence of moral rights. Economic rights are a consequence of moral rights, which in turn are generated by originality, not mere effort. The decision to protect original content, and not carefully generated content, is not accidental. Copyright is meant to protect the embodiment of the human spirit and the materialisation of personal creativity, not the intangible results of work and effort.

The key, in our view, is that what the AI ‘learns’ from the works it gobbles up are strictly technical factors. It therefore neither understands nor takes advantage of the dimension we want to protect, which is the expression of the human spirit.

Can an AI-generated work impress us? Of course it can. We can be moved by the most banal things, giving them a meaning they don't really have intrinsically. But the fact that an AI-generated work stuns or enthralls us should not make us forget its mathematical origin.

At this point, in our view, we see that the answer to a question that in 2018 would have seemed like science fiction is to be found in the principles of law. The difficulties in establishing a royalty for the benefit of authors of works used by the IAG perhaps indicate that such a royalty should not, in fact, exist.

Perhaps thanks to the commodification of content generation we are beginning to differentiate between what it means to ‘produce’ exploitable content and what it means to express the personality of the author. Perhaps the error in our intuition is the erroneous premise that the artist's contribution of value resides only in his or her ability to generate content that can be exploited economically.

Just as the advent of photography changed painting, the Gen AI will change art. It remains to be seen whether we are descending into the hells of a world that will cease to value art, or whether, on the contrary, we are moving towards a society that places value on an artist retaining a monopoly on his or his aesthetic discourse.

Footnotes

- To cite just one of many voices: Transparecy obligations are essential elements of the AI Act: "Transparency shall apply at the level of ingestion of copyright-protected works by AI systems. Collective authorisation/licensing shall identify the works used for the authors’ information and for them to receive their associated remuneration. In addition, a summary of the training data protected under copyright law shall be published by the AI companies for the users’ information".

- As any commercial lawyer will know, the shareholder's right to information must fulfil an instrumental purpose of the right to vote. We are not not saying that these cases we have compared are legally linked, we are saying that the underlying reasoning is the same. If such information is requested, there must be a reason.

- We wonder to what extent it makes sense to use these Latin terms. When we reread what we have written, it sounds like unnecessary hypercriticism that distances the article from the reader. But, on the other hand, replacing it with "Changing what needs to be changed" or similar formulas, as well as being less aesthetically pleasing, removes from the expression the connotations that we jurists attribute mutatis muntandis. In short.

- Probably using an automated detection tool for infringing images on the internet.

Leave a Reply