Footnotes

- Forgive me for being redundant.

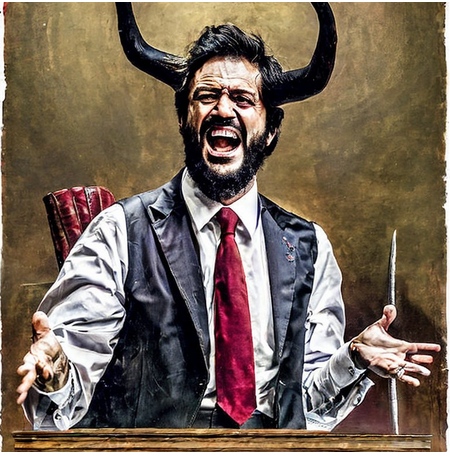

- Generated using the Stable Diffusion model, available at: https://beta.dreamstudio.ai/generate. Note that the eight images generated show a "lawyer" (a term that does not determine gender) as a white male, approximately 35 years old, with a suit and tie and brown hair combed to the side.

- Such as those available at https://stable-diffusion-art.com/prompt-guide/ and https://www.xataka.com/robotica-e-ia/guia-practica-para-escribir-mejores-prompts-midjourney-desbloquear-su-verdadero-potencial

- Prompt: Half demon half lawyer in trial screaming angrily at the camera, red skin and horns and with a three-piece suit with a purple tie, detailed clothing, ultra realistic illustration, Santiago Caruso, artstation, sharp focus, dramatic, low angle shot. Negative Prompt: un-detailed skin, semi-realistic, cgi, 3d, render, sketch, cartoon, drawing, ugly eyes, (out of frame:1.3), worst quality, low quality, jpeg artifacts, cgi, sketch, cartoon, drawing, (out of frame:1.1) Making prompts is an art in and of itself ,wink-elbow-wink.

- Paying for a prompt may not be as absurd as it may seem, considering how cheap they are and the time we can save if we find a reference that is close to what we are trying to generate, such as these typically American mascot team logos: https://promptbase.com/prompt/sports-logo

- One of the recommended orders to elaborate a prompt is the following:1.Type of image 2. Description of the main object. 3) Environment and other details 4) Style details 5) Technical parameters (proportion, stylization level, model, etc.).

- Estas serían las reglas que dictan cómo determinadas palabras, estilos o artistas serán interpretados por cada sistema de IA o si serán siquiera comprendidos. For example, before using the name of a certain artist as a style variant, we will have to determine whether the AI model in question knows it and will therefore take it into account. We should also follow some basic recommendations, such as the use of precise adjectives (scary instead of "very scary"), preference for the use of positive rather than negative adjectives, and a long list of etceteras.

- For computer programs, see Article 1(3) of Council Directive 91/250/EECand, now, Article 1(3) of Directive 2009/24/EC. For photographs, see Article 6 of Council Directive 93/98/EEC and, now, Article 6 of Directive 2006/116/EC. For databases, see Article 3(1) of Directiva 96/9/CE. As summarized in the article Copyright at the CJEU: Back to the start (of copyright protection) Eleonora Rosati, Developments and Directions in Intellectual Property Law. 20 Years of The IPKat (Oxford University Press: 2023), which is an excellent and relatively brief summary of the jurisprudential developments that have been permeating the concept of "work" in community law.

- The discussion of whether a "prompt" should be considered software (insofar as, strictly speaking, it serves to give instructions to the machine, as if it were a high-level programming language is as interesting as it is sterile, since the aforementioned Article 1(3) of Directive 2009/24/EC requires that the code be "the author's own intellectual creation". All roads lead to Infopaq

- In the previously cited article Copyright at the CJEU: Back to the start (of copyright protection), is stated that: "The definition thus provided, by requiring that the subject matter be “expressed”, contains an implicit reference to the idea/expression dichotomy. In imposing the conditions of precision and objectivity, it also clearly borrows from trade mark law (this is evident if one reads the AG Opinion in that case53) and its representation requirement. All this further implies that there should be no element of subjectivity in the process of identifying the protected subject-matter. .

- Although without reasoning its decision, the U.S. Copyright Office has said in its document Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence “While some prompts may be sufficiently creative to be protected by copyright, that does not mean that material generated from a copyrightable prompt is itself copyrightable."

- Among others, it is worth mentioning STS 588/2014 of October 22 (ECLI:ES:TS:2014:4623), SAP Madrid 67/2016, February 19, 2016 (ECLI: ES:APM:2016:2280), paragraphs 28-30, SAP BCN 147/2006 (ECLI:ES:APB:2006:3390) FJ Eleventh. The greatest exponent of the foregoing is SAP Madrid 269/2016, of July 8 (ECLI:ES:APM:2016:12864) when it states: “En definitiva, dado que "In short, given that the comparison is made between a television format and an audiovisual work, what must be determined is whether the latter involves, in substance, an application or execution of the plaintiffs' television format,(...)",(...)".

- In this sense, the USCO's decision on the registration of the AI-generated comic "Zarya of the dawn" argumenta lo siguiente para denegar la autoría de la Sra. Kashtanova sobre las imágenes del cómic en cuestión.:"The fact that Midjourney’s specific output cannot be predicted by users makes Midjourney different for copyright purposes than other tools used by artists. (...) Because Midjourney starts with randomly generated noise that evolves into a final image, there is no guarantee that a particular prompt will generate any particular visual output. Instead, prompts function closer to suggestions than orders, similar to the situation of a client who hires an artist to create an image with general directions as to its contents."

Leave a Reply