Footnotes

- Is Netflix a Technology Company? Exploring Its Impact and Role in the Industry, The Enlightened Mindset (lihpao.com).

- See, for example, the following Wikipedia article on 'Artificial intelligence Art'.

- “An AI Prompt is any form of text, question, information, or coding that communicates to AI what response you’re looking for. Adjusting how you phrase your prompt, AI could provide varying responses”, What is an AI Prompt?”, coschedule.com.

- And this is extrapolable to almost any other field of knowledge, see, for example, the evolution of programming languages from binary to high-level programming languages like JavaScript, with a syntax increasingly closer to human cognitive capacity.

- See, for example, "Why tech billionaires like Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos are all investing in biotech startups that want to link your computer directly to your brain”, Business Insider India.

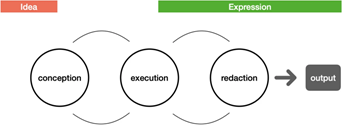

- Image No. 1. Diagram extracted from the article Copyright and Artificial Creation: Does EU Copyright Law Protect AI-Assisted Output? P. Bernt Hugenholtz, João Pedro Quintais. Springer, showing the iterations of the creative process.

- Image No. 2. Labeling of the phases 'conception', 'execution' and 'redaction', based on whether they are phases carried out by humans or by machines.

- Image No. 3. Back cover of issue No. 346 of Món Jurídic magazine.

- Access to the resolution of the US Copyright Office (USCO) through the following link.

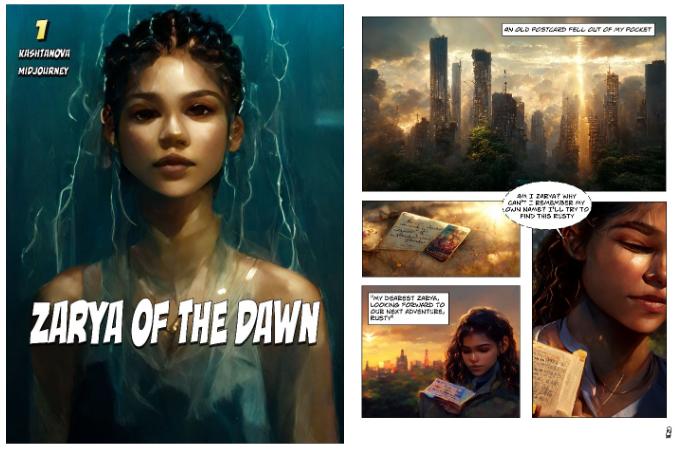

- Image No. 4. Cover of the comic Zarya of the Daw (left) and page #2 of the comic (right). ©Kristina Kashtanova

- This is reflected by the Office on numerous occasions: “Courts interpreting the phrase “works of authorship” have uniformly limited it to the creations of human authors”; “the Office “will refuse to register a claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work”. For this purpose, indirect reference is also made to the case of the Naruto Seflie, in as much as it is said: “providing examples of works lacking human authorship such as “a photograph taken by a monkey".

- La Propiedad Intelectual de las obras creadas por Inteligencia Artificial, Thomson Reuters Aranzadi, 2021, pages 64 to 72.

- Case C‑5/08 – Infopaq International v. Danske Dagblades Forening (2009) ECLI:EU:C:2009:465 ((Infopaq)).

- Case C-683/17 – Cofemel — Sociedade de Vestuário, S.A. y G-Star Raw CV (2019) ECLI:EU:C:2019:721 (Cofemel). § 30.

- Case C-145/10 – Eva-Maria Painer v. Standard VerlagsGmbH (2011) ECLI:EU:C:2011:798 ((Painer)), § 98.

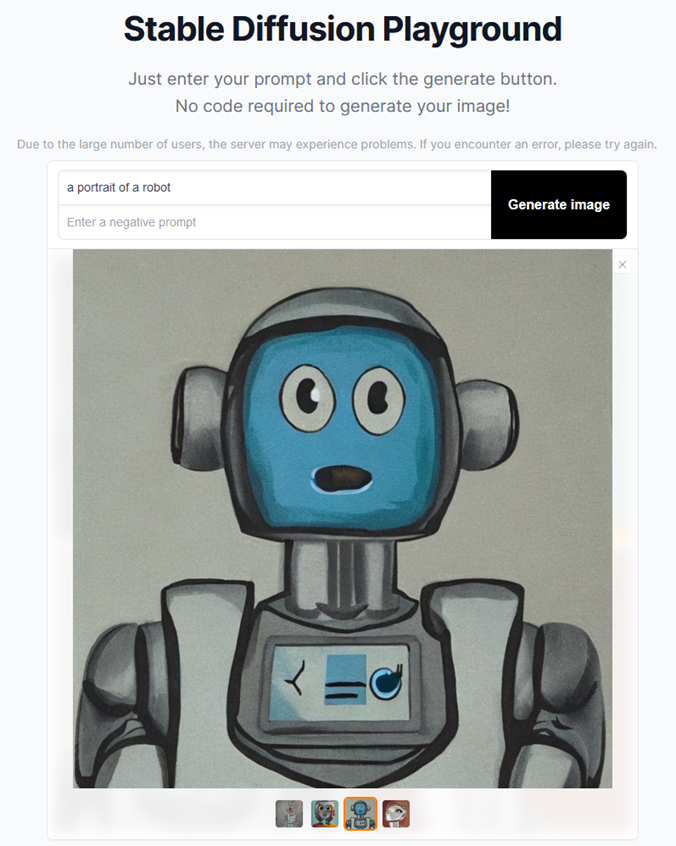

- Image No. 5. Example of one of the results generated by Stable Diffusion when using Prompt #1

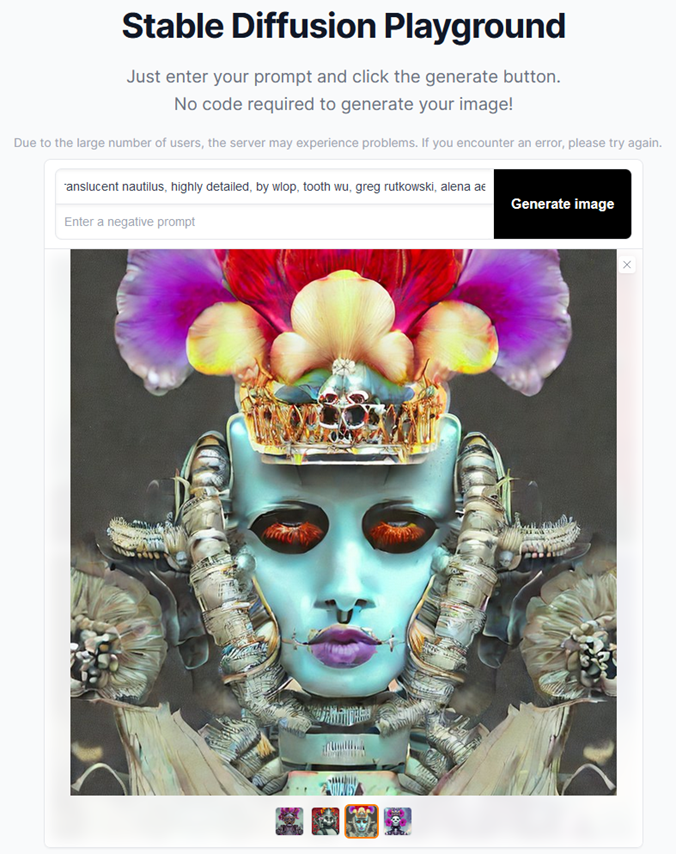

- Image No. 6. Example of one of the results generated by Stable Diffusion when using Prompt #2

- Prompt No. 2. Retrieved from Stable Difussion prompts search engine.

- SAP nº 24/2008, de 22 de enero de 2008 (ECLI:ES:APIB:2008:106) (Barceló).

- Décisión du 08 Juillet 2022 (Caso Druet y Cattelan).

- We are talking about Infopaq's famous 'author's own intellectual creation', (Infopaq), Cofemel's 'free and creative choices' criterion Cofemel, or Painer's 'personal touch' contribution (Painer).

- The famous historian Yuval Noah Harari, in his work 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, speaks, in his opinion, of the relevance that thinkers, philosophers and historians should take in the search for answers to the great questions of the human being; otherwise, these answers will be given by the engineers who create technology, without their participation of any kind. See, for example, the classic debate on the criterion for prioritizing the risk of the autonomous car.

- This is what Professor Pablo Fernández Carballo-Calero, in his aforementioned work 'La propiedad Intelectual de las obras creadas por Inteligencia Artificial', in the section where he talks about 'Los fundamentos del derecho de autor y su incidencia en las obras creadas por AI' distinguishes between the following three substantive theories: (i) Locke's 'labor theory', which defends property as a reward for the fruit of the work developed by the author, (ii) the 'personalist theory', which places value on the personality of creators, and (iii) the 'utilitarian theory', which examines intellectual property rules in terms of their effectiveness and ability to promote the welfare of society by increasing its cultural heritage.

- HRISTOV, K. “Artificial intelligence and the copyright dilemma".

Leave a Reply